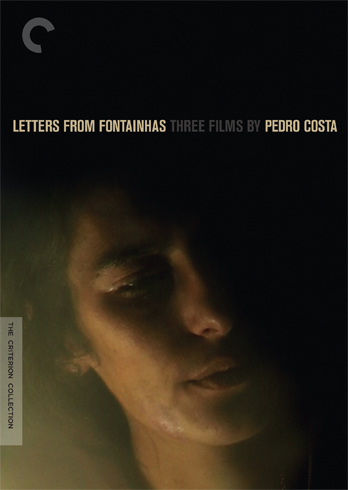

Letters from Fontainhas

Thursday, March 11, 2010 at 11:44AM

Thursday, March 11, 2010 at 11:44AM  I cannot overstate the importance of Pedro Costa in film history or current global cinema — nor can I here sum up the importance of these three films which are being given a long overdue US release by Criterion this month. Suffice it to say that many critics have said that Costa has reinvented every aspect of filmmaking and has created completely singular, honest and beautiful works since his earliest films on 35mm to his latest landmark DV pieces.

I cannot overstate the importance of Pedro Costa in film history or current global cinema — nor can I here sum up the importance of these three films which are being given a long overdue US release by Criterion this month. Suffice it to say that many critics have said that Costa has reinvented every aspect of filmmaking and has created completely singular, honest and beautiful works since his earliest films on 35mm to his latest landmark DV pieces.

In discussing the earliest of these three films, Ossos (1997), Costa himself as well as many critics are preoccupied by discussing the failures of a traditional 35mm film production in acheiving the filmmaker's goal of blending into the environment of the real Lisbon neighborhood of Fontainhas and preserving the texture and natural quality of the residents and performers — all issues which Costa goes on to dramatically address in his subsequent DV films. However, the fact remains that if not viewed in comparison to Costa's subsequent films but all precedent film history, Ossos is an undeniable masterpiece of naturalism, realism, and the rarely attempted or successful project of creating films that are simultaneously poetic and political. Shot by the brilliant cinematographer Emmanuel Machuel (L'argent, Um Filme Falado, Casa de Lava) in liminal greys, blues and blacks with almost no artificial lighting, the film inhabits the damaged and painful lives of the residents of Fontainhas through a revolutionary collaborative and self-aware artifice of style and structure.

But this was not enough for Costa, who was compelled to become a resident of the Fontainhas and generate the material with the performers in an organic yet imaginitive two-year process that became the unprecedented masterpiece, No Quarto da Vanda (2000). While completely eschewing the institutionalized practices of film production — shooting without lights, script, actors, crew, or even a noticible division between filmmaker and subject — Costa elevates the most impoverished material to the emotional and visual tenor of high-renaissance painting through what I consider the most original and talented "eye" in cinema today. This is a cinema whose great depths of meaning and heights of intent are only made possible through the divestment of power structures and official culture — which, for my money, is the most important kind of filmmaking happening in the world today.

Juventude em Marcha (2006) takes this progression into a third, reflective and elegaic phase, treating the collaboratve construction of this narrative space within the real physical locations of their neighborhoods as an an epic meta-text of the everyday that is equally psychological, poetic and political. In an extraordinary technical and aesthetic feat, Costa ramps up the symbolic grandeur of the characters while simultaneously heightening the alienating self-referential stylistic elements: what was the near lack of film lighting in Ossos, then the total lack in Vanda, is in Juventude an ecstatic use of DIY expressionistic and highly stylized film lighting acheived by the use of many pieces of reflective materials and mirrored surfaces, bouncing and cutting the natural light into eye-popping tableaus. Juventude puts institutionalized commercial film production methods to shame twice over: the honesty and poverty of his production methods proudly become integral to and involved in the meaning of the film at the same time that he is creating images far more innovative and stunning than the biggest-budgeted, hi-tech films currently being made.

Some have likened what Costa has done in this trilogy to the development of abstract expressionism in painting — which I would have to disagree with given that movement's all-too-comfortable repurposing as corporate lobby decoration. If I had to find an analogy in traditional high-artistic media, I would say that Costa has done to film something like what Samuel Beckett did to the novel in his famous trilogy — stripped of institutionalized and commercial techniques, infusing dazzling gestures of prosity with what was before hidden from view by established codes of representation, the work of generating radical subjectivity can begin — if we seek it out. You can order (or pre-order) the box set from the Criterion website.